Top 10 Scientific And Historical Facts About Bees

Mankind’s relationship with bees goes beyond the love affair with honey. The sweet treat has its own unusual properties and claims, but bee venom, genes, and fossils are changing many scientific fields. Ancient therapies return to heal (or kill) modern patients, and famous prehistoric events lurk in the insects’ DNA. There’s the oldest honey farm that was surprisingly advanced and the oldest bee that evolution hated. It is easy to overlook a buzzing individual in the garden, but bees’ history and influence remain remarkably complex.

10 Why Honey Lasts Forever

The recipe for immortality is simple—acidity, no water, and a touch of hydrogen peroxide. At least, this works for honey. Many a surprised archaeologist has stumbled upon the sweet snack and found it edible after thousands of years. Honey has one enemy—water. Should water get into it, the honey will spoil. Nectar is mostly water, and this flowery ingredient is also the first step in the honey-making process. Remarkably, bees remove the water from nectar by fanning it dry with their rapid wing beats. After bees regurgitate nectar into honeycombs, they leave behind a stomach enzyme that breaks down the fluid. One by-product is hydrogen peroxide which, along with honey’s natural acidic and waterless state, prevents organisms from surviving inside the delicious goop. This ability to smother infections was the reason why many ancient cultures used honey as a natural bandage for open and burn wounds. If honey remains sealed against water, there is no reason why it cannot last for as long as the lid holds.

9 Ancient Snacks For Bees

In 2015, researchers looked at what kind of pollen clung to the fossil bees from the extinct group called Electrapini. Found in Germany and aged 44–48 million years, the bees revealed their snacking habits outside the hive. Bees travel great distances to gather pollen to feed their young. These grains are compacted into balls against the bee’s back legs and are known as pollen baskets. During the marathon flight sessions, the adults must also eat constantly to replenish energy. The pollen on the ancient bees revealed that the nectar-loving adults did not shy away from leaving their usual pollen areas to search for nectar for themselves. Finding one kind of pollen in the baskets (for the babies) and a multitude of other plants’ pollen on their bodies (picked up wherever they consumed nectar) is scientifically important. It is the oldest proof that bees collect food for themselves and their offspring during the same flight. The discovery is also crucial to the survival of modern bees. If researchers can apply this knowledge to find out what flowering plants best support bees, these food sources can be better protected.

8 What Ancient Mead Tastes Like

In 2000, archaeologists dug into a grave in Germany. The burial mound dated between the seventh and fifth centuries BC and contained the weapons of a long-decomposed man. A cauldron lay at his feet (or where they once were). Inside were the 2,500-year-old remains of something dark. Curious to know what was so valued that it had to accompany the man into the afterlife, researchers decided to test it. The sediment turned out to be mead, a honey-based alcoholic drink. Taking things a step further, brewers were brought in to recreate the ancient refreshment in 2016. The Iron Age booze had five ingredients: honey, yeast, barley, and the herbs mint and meadowsweet for flavor. When tasted, it was drinkable and in the vicinity of a dry port that lacked sweetness. Surprisingly, the mint came through very strongly with only a hint of meadowsweet and no honey. The lack of a honey taste was not surprising. The ingredient had converted into a good alcoholic kick. Even so, the consensus was that the Iron Age mead would probably not become popular at bars today.

7 New Cuckoo Bees

Cuckoo bees were named for the bird that deposits its eggs in the nests of other species. This kind of bee doesn’t have a nest and leaves its kids inside the hives of settled swarms. A cuckoo baby bee kills off the resident bee larva and consumes the pollen stored for the larva. Once grown, the invader abandons the adoptive nest to live a solitary life. In 2018, scientists discovered that cuckoo bees were good at hiding in museums, too. Amazingly, when researchers scoured through bee collections in North American museums, 15 new cuckoo bee species showed up. They all belonged to the Epeolus genus, and the discovery pushed the known North American species in this group up to 43. The newcomers resembled wasps rather than bees. Although some were clearly unidentified types, others looked so similar that only DNA tests revealed their unknown status. Finding new bees in old collections could only be the start of adding more species to the 20,000 already identified.

6 Romanians Love Their Bees

In Romania, the restorative properties of the hive are more than just an alternative lifestyle craze. It is serious business. Due to its past history of poverty and communism, Romania never developed as fast as most other countries. As a result, nature remained diverse and the people held onto folk remedies. Many qualified doctors and bee product researchers come from families where honey was used as traditional medicine. Today, Romania actively keeps apitherapy alive in villages and in the science laboratory. Considered the “oldest pharmacy in the world,” apitherapy includes venom, honey, propolis, and even pollen. Going back to ancient Greek and Roman times, it was hailed back in the day as a wound healer, aid to indigestion, and more. Romanian treatments are said to combat diseases and conditions like multiple sclerosis, sore throats, weak immune systems. The country is not put off by the medical community, which largely is unconvinced by apitherapy. Each town has a so-called plafar, a pharmacy that specializes in bee products. Bucharest opened the world’s first apitherapy medical center back in 1984. A census in 2010 also counted 42,000 beekeepers happily attending 1.3 million colonies of bees.

↚

5 Ancient Brain Booster

Around 2.5 million years ago, hominids broke away from the apes by developing bigger brains. Something happened to these early hominids that enlarged their gray matter even more, and they developed the mental faculties that separated them from animals. Researchers believe that food—in particular, honey—played a big part in the evolution of this human trademark. Though honey is certainly not the only thing that nourished brain power, there is a strong argument that its properties acted like a booster. Apart from other critical foods like meat, honey had glucose and dense energy that were perfect for brain development. Back then, the only available source was wild honey and that was even better. The wild variety is packed with bee larvae pieces, minerals, vitamins, fat, and protein. There is no evidence of honey-enriched brains in the fossil record, but looking at people and apes today suggests that the theory is sound. Wild honey remains a huge part of several tribal diets around the world. Primates also continue to use inventive ways, tools included, to break into beehives.

4 People Who Love Bee Venom

It is called Bee Venom Therapy, a practice that falls under apitherapy (medicinal uses of bees and honey). The treatment is ancient and painful. The doctor, or whoever qualifies to oversee this bizarre method, angers a bee before letting it sting the patient. The bees are usually placed on trigger points. During a visit, the person receives multiple zaps from a small swarm. How the venom is supposed to help for things like scarring, inflammation, anxiety, and even serious conditions like high blood pressure and multiple sclerosis is unknown. However, believers (including celebrities) stand strong behind the treatment. Those who are scared of the stings also have the option to be injected with the venom, but the therapy is far from safe. The so-called benefits still need to be scientifically proven. In 2015, a Spanish woman suffered a horrific case of anaphylactic shock. She had no prior history of a bee allergy and underwent the treatment for two years. During the last visit, a sting caused a massive stroke and organ failure, killing her.

3 Oldest Bee Farm

At Tel Rehov in Israel’s Jordan Valley, 30 clay cylinders were unearthed in 2010. They held ancient honeybees but not as traps. The insects lived inside the containers, a fact backed up by tiny doors and the fossils of different individuals and life stages. Among the remains were worker bees, drones as well as pupae and larvae. The hives were around 3,000 years old and, oddly, within a courtyard inside a dense urban area. Bees can get nasty, especially during routine honey removal. The reason behind the risky location is not fully understood. Perhaps, honey was so precious that the location kept the “factory” safe from theft or natural damage. Interestingly, the bee species was different from those living in Israel today. Instead, the fossils closely matched Turkish bees. The farm was the first archaeological evidence of beekeeping. Also, the foreign species (probably imported for better quality) and the elaborate courtyard showed that the practice was already highly advanced in Israel 3,000 years ago.

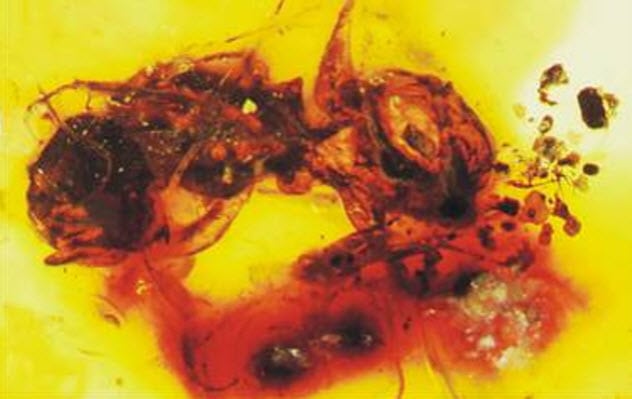

2 Oldest Bee Was A Dud

Amber is a semiprecious stone that often harbors fossils. Thanks to its translucent and preservation qualities, amber makes million-year-old specimens appear freshly trapped in yellow glass. Recently, another frozen-in-time specimen was found—the world’s oldest bee. The amber piece was mined in the Hukawng Valley of Myanmar (Burma). Inside was a bee that died around 100 million years ago. Astonishingly, the previous oldest bees were about 40 million years younger. This allowed scientists a good look at the “first bee.” It was male, unrelated to any modern species, and ate pollen. It was not a honeybee. Named Melittosphex burmensis, it was five times smaller than today’s honeybee and shared several physical traits with carnivorous wasps. The tiny creature could help scientists better understand the era’s flowers, four of which were trapped with the prehistoric bee. Unfortunately for Melittosphex burmensis itself, the lack of living descendants suggests that the species was an evolutionary flop that went extinct before it could contribute as an ancestor to modern bees.

1 Dinosaur Extinction In Bee DNA

The great dinosaur extinction event is a well-known fact that happened around 65 million years ago. Images of giant creatures like Tyrannosaurus rex dying in the disaster (thought to be a space impact) make it easy to forget that other non-dinosaur species also perished. One of them may have been the ancestors of today’s carpenter bees. In 2013, a study looked at the latter’s DNA and found something unexpected. A genetic anomaly possibly showed the effect of the dinosaur extinction event on the carpenter bee lineage. Four kinds of these bees showed the exact same thing: Around 65 million years ago, evolution stopped dead. No genetic diversity happened for close to 10 million years. To scientists, something like this indicates a mass extinction inside a species’ history. The similar timing suggested that the bees were wiped out during the same disaster that crushed the dinosaurs and 80 percent of all Earth’s species.

No comments:

Post a Comment